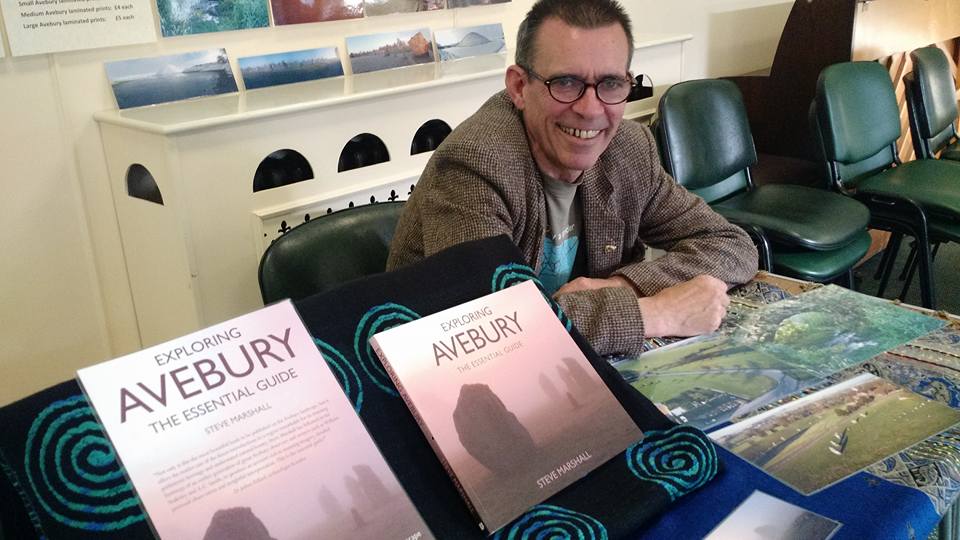

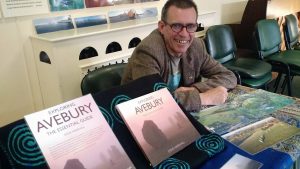

There is now a definitive, ‘essential guide’ to Avebury, the world’s largest stone circle, situated in Wiltshire in the UK. Researched and written by Steve Marshall, Exploring Avebury, has received rave reviews since its publication in May 2016. Historian, Professor Ronald Hutton, says ‘Exploring Avebury is really excellent, being quite clearly the best current introduction and guide to the whole monumental complex: up to date, consistently fair-minded, and superbly illustrated’.

There is now a definitive, ‘essential guide’ to Avebury, the world’s largest stone circle, situated in Wiltshire in the UK. Researched and written by Steve Marshall, Exploring Avebury, has received rave reviews since its publication in May 2016. Historian, Professor Ronald Hutton, says ‘Exploring Avebury is really excellent, being quite clearly the best current introduction and guide to the whole monumental complex: up to date, consistently fair-minded, and superbly illustrated’.

I first met Steve on the Sacred Scotland tour in 2014. When he talks about his research for the book, you soon see that he thinks outside the square and has an inquisitive mind and a quirky sense of humour…great assets when speculating about how 5,000 year old sacred sites were used. Steve joins us at Avebury and West Kennet longbarrow each year on the Merlin’s Britain tour. Towards the end of this interview, he describes the unique experience you can expect if you join us on this tour.

So, how does Steve describe himself? Is he an archaeologist, historian or something else?

STEVE: Well, I’m not a trained archaeologist, I describe myself as an independent researcher. Archaeologists are very nice to independent researchers, these days. There’s a taboo against calling us amateurs! We pop up everywhere. For example, Neil Wiseman has written an amazing new book about Stonehenge, yet he’s an American, living on Cape Cod! He’s managed to do a huge amount of detailed, cutting-edge research from 2,000 miles away.

LINDA: What sort of interaction do you have with archaeologists?

STEVE: I’m in touch with many of the top archaeologists who work on Avebury and Stonehenge. They’re very supportive and have given me lots of help and advice. For instance, Mike Parker Pearson, the big expert on Stonehenge and Durrington Walls, went through my book and checked that all the archaeology was accurate. David Field, a well-respected archaeologist and writer, gave me lots of notes on early drafts. Among independent researchers, you sometimes encounter a ‘me versus the world of archaeology’ attitude, as though archaeologists are the enemy. They’re not at all. They recognise that people who live close to sites such as Avebury, can do field work that professionals can never do because it’s too time-consuming.

LINDA: So what have you done by way of field work that is different to what an archaeologist would do?

STEVE: To me, Avebury comes alive in the winter, which seems wrong, but it’s because springs and rivers are seasonal and depend on the water table rising with rainfall. Summer is when most people visit Avebury, including archaeologists, but the springs don’t run in the summer and the rivers are dry. Because I lived just a couple of miles from Avebury for 10 years, I was able to go at all times of day and in all seasons and weathers. Unfortunately, those are the times when it’s raining and frozen! Not many people explore Avebury under those conditions, but that’s when I find it interesting and that’s how I discovered all the springs around Silbury Hill.

Click here to hear Steve talking about his field work experiences. He starts by describing years of hanging about with a tape measure in the Red Lion Pub in Avebury to work out fluctuations in the water table level in all seasons. Then, his rather inventive way of capturing aerial shots by mounting his camera under a homemade helium balloon! You can’t actually see it in this photo, but the camera is attached at the bottom of the balloon.

LINDA: I’m curious to know what you thought or felt the very first time you went to Avebury.

STEVE: Oh..that’s about 25 years ago when I was living in London and house-hunting in Wiltshire. I ended up moving from the east end of London to Alton Barns, the centre of crop circle country. I’d not heard of Avebury and someone suggested I take a look. I was staggered at the size of it. When you park at the National Trust car park, walk through onto the High Street and see the ditch and bank and cross-section, you can’t help being amazed at the scale of the earth work. Then it dawns on you, that the people who made over 4,000 years ago, did so with antler picks and other such tools. And now it’s only half the size and depth it was then.

LINDA: So it didn’t evoke a particular feeling?

STEVE: No, not really, I was just amazed at the amount of history sitting there. I tend not to feel the ‘vibes’. I spend a lot of time going around Avebury with people who do, but myself, I don’t experience it that way.

LINDA: Interesting. You’ve done a massive amount of ‘independent research’. What made you embark on such an undertaking?

STEVE: I started working on it seven years ago after I’d been living near Avebury for a long time. The original idea was to report on all that was known about Avebury, with some of the theories of what it was about. I had no intention of coming up with new theories, I just wanted to present ‘the facts’, which meant I spent a lot of time doing field work. For example, I explored 20 long barrows which are within a five mile radius of Avebury, many of which are ruined. I got so wrapped up in the field work that a couple of years went by and I lost track of the ‘presenting the facts’ thing, because, by then, interesting findings were coming out of my field work.

LINDA: What do you consider the most interesting or new contribution you’ve made to the body of knowledge about Avebury?

STEVE: The connection to water is my big thing – the fact that there’s a confluence of two rivers to the west of Avebury – one river flowing south and the other flowing east. When you look at henge sites and other Neolithic enclosures around Britain, this is a common pattern. There seems to have been something very important about river confluences and particularly ones where east and south meet.

LINDA: Have you come to any conclusions about that?

STEVE: Yes, I think it’s to do with the sky. East is where both the sun and moon rise and the highest point is in the south. In many traditional cultures, east and south are seen as being ‘good’ and west and particularly north are seen as ‘bad’. North is the direction of death for lots of cultures because that’s where the sun and moon disappear and symbolically ‘die’. Interestingly, in lots of Indo-European languages, including modern Welsh, the word for ‘right’ and the word for ‘south’ are the same, which implies that the speaker is facing east, facing the sunrise. Also, broadly speaking, all long barrows face east. It’s important to realise that the water table was probably two metres higher in the Neolithic, so springs that are seasonal today may have been perennial when Avebury was first built. I discovered springs all around the ditch that surrounds Silbury which had never been noticed before.

LINDA: Silbury was constructed over a long period of time – what is it and why did people build it?

STEVE: There are about 250 layers of chalk inside Silbury. I think it was built directly on top of a spring. Excavations show that the very first layer was a shallow pile of gravel. If you were building on top of a spring, that would be a sensible thing to do because you’d have something firm to stand on. I think it symbolise a creation myth which is commonly found among North-American Indians called the earth diver myth. There’s nothing in the world but water, so the Creator sends an animal such as a beaver or a turtle down to the bottom of the sea to bring some mud back. From that he forms an island and makes all the land in the world. I’m not the only person who has come to this conclusion about Silbury.

LINDA: Looking at this wonderful photo you’ve taken of Silbury covered in snow, is that how you think it looked way back when?

LINDA: Looking at this wonderful photo you’ve taken of Silbury covered in snow, is that how you think it looked way back when?

STEVE: Yes, when you look at Silbury covered in snow, you’re seeing how it would have looked when it was freshly chalked. An historian friend of mine, Brian Edwards, suggests it’s rather like the chalk hill figures we see today around Wiltshire. They don’t stay white, they need scouring every year or few years because rain and weather wash the chalk down the hill. Scouring isn’t just getting rid of weeds, it’s more about putting a fresh coating of white rubble on it. Brian thinks Silbury became so enormous because every year or so, chalk was being added to it.

LINDA: Let’s go back to Avebury and your theories on how it was used and why it was constructed in four quadrants with an avenue, for example.

STEVE: The odd thing about the Avebury henge is that it has four entrances and for some reason they’re not aligned to the cardinal points. It would make a lot more sense if the north entrance pointed due north, but it’s skewed to the west and I have absolutely no idea why that is and no one else does either! Answers on a postcard please!

LINDA: For me, Avebury has a community feel, as though people would have used it for gatherings, ceremonies and celebrations. What do you think?

STEVE: It certainly suits that. For example, if you go to the Summer Solstice celebrations when the Kings Drummers play, you see a happy Avebury full of light, but it wasn’t necessarily that way. Remember it’s a henge and what defines a henge is that there’s a bank and ditch and the ditch is on the inside of the bank – the opposite to a castle with a moat. So it’s not defensive, it’s not keeping something out, it’s keeping something in, e.g. spirits, ancestors. We assume they’re benign, but they might not be. For instance, we assume the bones found in the West Kennet long barrow are those of a revered, high status family, but they may have been enemies put in there to stop them causing any trouble when they became spirits!

Sound and acoustics is another area I’ve explored. I’ve spent of lot of time recording echoes coming off the stones. When all the Avebury stones were there, I think the whole place would have been alive with echoes. If the ancients saw it as a place where spirits dwelled, the effect of sound coming back would be magical. Without an understanding of physics, they would hear echoes as spirits and ancestors speaking to them. The problem with researching acoustics today is the sound of aeroplanes over-head and heavy traffic noise. It’s hard to imagine what it was like 4,000 years ago. I recorded echo using a pair of hard wooden sticks. When you click them together you can hear really clear echoes coming off the stones, or you can if there’s no traffic noise. To record that cleanly, I went at the quietest possible time which is at 8 or 9 o’clock on New Year’s Day in the freezing fog! It was a completely different Avebury – I could hear any sound I made reflecting back from the stones.

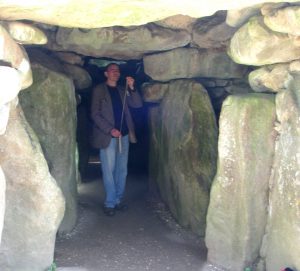

LINDA: Tell us about the acoustic work you’ve done in West Kennet long barrow.

STEVE: Yes, I did a lot of that in the middle of the night by torchlight! I soon discovered that when you’re in there on your own in the dark and make a sound, you get the impression there’s someone behind you. This is due to low frequency resonance, sound that’s too low to hear like 9 Htz, nine vibrations a second. It’s a bit like when you blow across a bottle and it produces a note. Resonating the passage of West Kennet long barrow produces a note that’s too low to hear, but we can feel it. It’s quite unsettling, you definitely get the feeling that there’s a presence. I think the barrow wasn’t just a tomb. Long barrows in general were used for initiations and rites of passage. It’s likely that adolescent children were put in the end chamber and the passage was resonated, producing altered states. It’s to do with brain wave entrainment. For example you can produce very low frequencies that your brain will lock into, for example, alpha waves that are associated with deep meditation states.

I recreated this at the 2016 Megalithomania Conference in Glastonbury Town Hall where I played a very low frequency resonance and the majority of people in the audience felt as though they were going up in the air, or levitating! Imagine what it would have been like if you were an adolescent put in the West Kennet long barrow, maybe deprived of sleep, maybe even given plant hallucinogens, and more importantly, being told that something unique was going to happen and it’s going to be the only time in your life that it does.

LINDA: You’re very well qualified for this acoustic research, aren’t you?

STEVE: Yes, I was a professional musician for 30 years and a sound engineer. I used to make soundtracks for BBC documentaries. For a while I was in the BBC Radiophonic Workshop where they did the Doctor Who music.

LINDA: Do you take people on guided tours of Avebury and West Kennet long barrow?

STEVE: Yes, and I angle it towards unusual things, stuff that other tour guides don’t do. For example, on the ‘sound’ tour we go around the henge and listen to the echoes. There are a few stones that have small holes in them and if you hit them in the right way you can play tunes on the stones! And I take people to the West Kennet long barrow, put them in the end chamber and they can experience what happens when the passage is resonated.

I use a bullroarer to do that. It’s the oldest sound making device or musical instrument in the world. Just about every culture in the world invented the bullroarer independently. It’s a fish-shaped piece of wood which you whirl around on a string and it produces a low frequency, humming noise. But it also produces frequencies that are too low to hear. If you whirl the bullroarer around outside the entrance of the West Kennet long barrow, people in the end chamber can really feel the low frequency vibrations. I’ve tried this at other chambered tombs, for example, Newgrange in Ireland and Maeshowe on Orkney. It produces the same effect in all of them. I can’t prove that Neolithic people used bullroarers because, being made of wood, they would have rotted away. But there are hints that things resembling bullroarers have been found in round barrows near Avebury. I also discovered that if you tie a piece of string to flint knives that are found everywhere in the landscape, you can produce the same sound as a bullroarer. So I think there’s a case for saying that Neolithic people did use a bullroarer.

I use a bullroarer to do that. It’s the oldest sound making device or musical instrument in the world. Just about every culture in the world invented the bullroarer independently. It’s a fish-shaped piece of wood which you whirl around on a string and it produces a low frequency, humming noise. But it also produces frequencies that are too low to hear. If you whirl the bullroarer around outside the entrance of the West Kennet long barrow, people in the end chamber can really feel the low frequency vibrations. I’ve tried this at other chambered tombs, for example, Newgrange in Ireland and Maeshowe on Orkney. It produces the same effect in all of them. I can’t prove that Neolithic people used bullroarers because, being made of wood, they would have rotted away. But there are hints that things resembling bullroarers have been found in round barrows near Avebury. I also discovered that if you tie a piece of string to flint knives that are found everywhere in the landscape, you can produce the same sound as a bullroarer. So I think there’s a case for saying that Neolithic people did use a bullroarer.

LINDA: Finally, tell us aout the Exploring Avebury website.

STEVE: Earlier versions of the book contained a mass of detailed information coming from my research and field work. Through the review and editing process, I came to see that it was better to find another home for the detailed research…the Exploring Avebury website. It’s a great resource for anyone interested in Avebury, and archaeology in general. There you’ll find additional material for each chapter in the book, including extra text with notes, references and web links. There are also bonus chapters and videos of some unique features, such as the acoustics of the West Kennet long barrow.

Over to you!

Have you been to Avebury? If so, tell us about your experience. Take a look at the Exploring Avebury website and let us know what you think of the information Steve is sharing so freely. We’d love to hear from you.